Fantasy

Excerpts from Xylandova

Guinevieve was free-falling through layer upon layer of cloud. Blinded in the soft grey and bright whites, her heart only slowed as she dropped, down and down, tucked in invisibility, peacefully alone in her descent. Wrapped neatly in mist and fog, she breathed deeply and filled her lungs with the thick dew of a morning in Xylandova. The clouds thinned; she was nearing the bottom, and the mainland would soon be splayed beneath her, green and dense and dark and foreign and nearly a mile of empty air between the mottled mystery and her, her horse, and her kingdom.

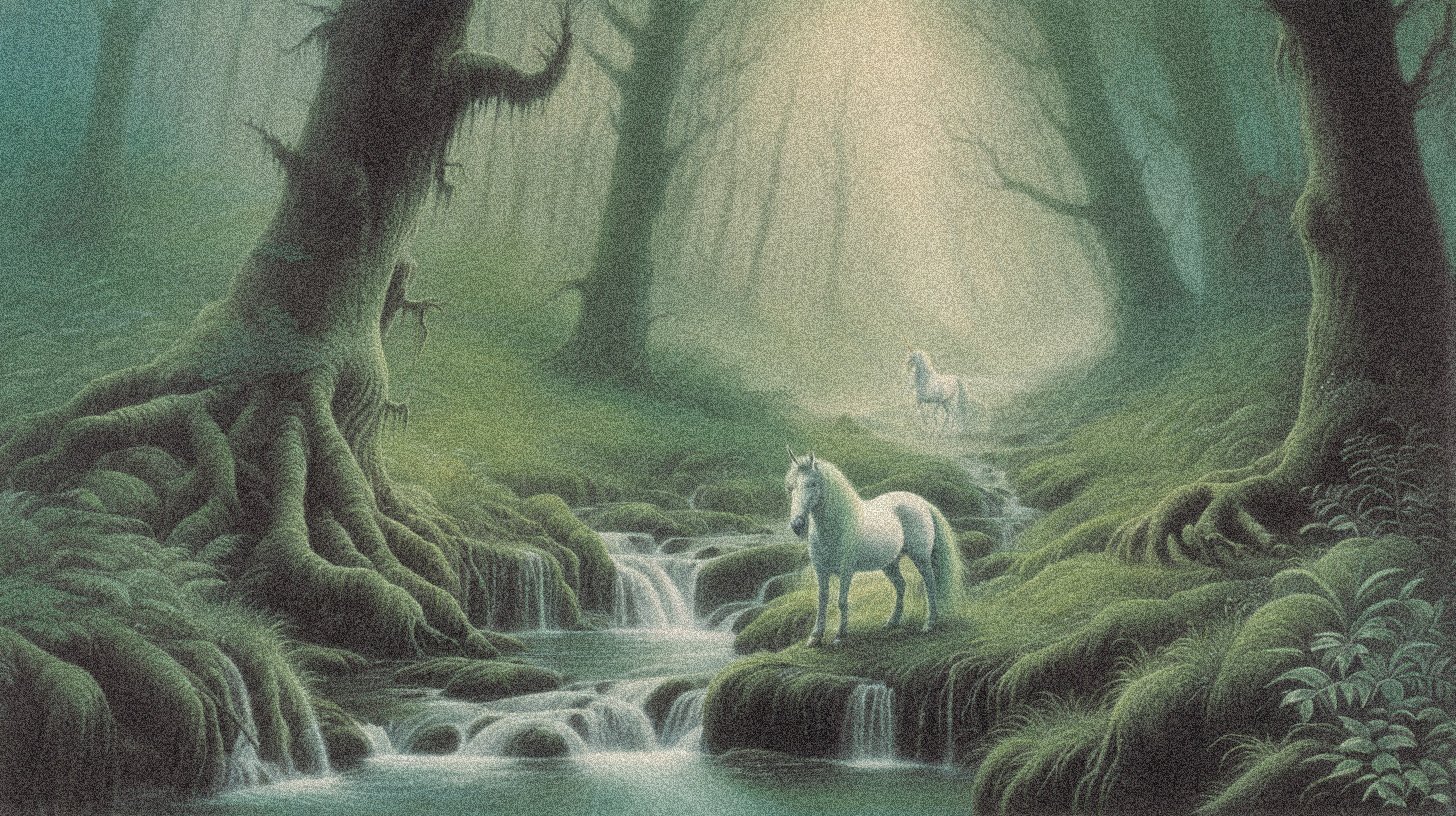

She let herself continue, the blanket of white became a thin veil, and she pulled gently on the reins, wanting the briefest glimpse of what existed—what she could only imagine existed in the tangle of forests, the ridges of the mountains, the water reflecting the pale pinks and slight orange of the rising sun. She was told it housed beasts, barbarians, creatures of unsavory design—but here, in the kind sunrise, she could only picture the small villages waking with the dawn, putting the kettle on as the flowering morning arrived with birdsong and warmth—the dew would dry.

Enough was enough—she granted herself small glances down to the mainland while riding in the morning but never lingered. She preferred not to let her imagination run off, preferred not to begin to long for things she didn’t understand and would never experience.

Guinevieve tugged the reins bridling her pegasus, Zephyr, and he rose back into the grey.

She was in no hurry to return to the castle. The knight assigned as her guard for the past seven years had acquiesced her need for pure solitude—her request to fly alone in the morning always emitted a sigh of protest, a hesitant muttering, and a pained restraint. Often, he would give her a few moments head start and follow silently on his black stallion, granting her only the illusion of independence, staying just out of sight, concealed in the semi-opaque cloud surrounding Xylandova for a half mile in all directions. Today, he itched on the edge of the land, the soft green grass crushed under his thick, armored sabatons, letting her ride completely alone.

Her father was dead. Her guard could not protest her desire to be left alone; he could not argue the look in her eyes as she told him, chin high, voice not quite accustomed to the hard edge her new position as queen required. He was staying grounded, stationary on the cliffside, waiting for the hidden sunrise to melt into midmorning spring gold below—he would only see the cloud shift from a slate grey to a brighter shade—and her to return to their meeting place.

She was not as anxious to return to him as he was for her to appear, long, brown, ashen tresses tousled from wind, and a dew staining a freshness on her round, freckled face, becoming more regal with age and title. She was a young queen, only twenty and five years of age, but the kingdom thrust upon her only days ago had already slimmed her pale cheeks and iced her playful, overly large blue eyes into a cold sapphire to parallel the stones on her crown. He could not deny her girlish beauty had become the timeless elegance of a cloud-dwelling queen, but after the morning rides since her father’s death, he could see the vigorous youth alight in her features, before closing like the petals of an evening primrose with the dawn.

As she climbed the misty void beneath her kingdom, pressing through clouds and clearing the rocky cliffs that tapered into a point at the base of the land, she drained the last dewdrops of peace she would taste for the day; like nectar, the sweetness of the water dusting the air, coating her skin, filling her lungs, settled her nerves. The underbelly of Xylandova fattened until she could see the outcroppings of rock jutting organically, signaling she was nearing the wide green expanse of the kingdom’s surface. Her mind emptied on her rides—it filled again as her decidedly tall, slim, mist-shrouded figure rose, each time, back to the land, the pale grey palace looming in its gentle neutrality as though it were something evil, something resembling the unfavorable castles dotting the mainland in swarms of dark magic, patrolled by wolves with red eyes and dragons heaving magma out of withered lips, keeping trespassers terrified and far, far away. Or so she had been told.

The delectable fragrance of the rock and cloud combined into a fresh minerality, and soon she was breathing the heavy scent of loam, moss, grass layering atop the effervescent essence of sky and water and stone. She was back.

Zephyr came bounding up the last stretch of vaporous desolation on expansive wings, beating wind into obedience, and landing, graceful as ever, on the bright green dusting of groundcover clinging to the very edge of Xylandova.

The wide opening narrowed instantly, the firelight teasing from just around a corner. Guinevieve locked eyes with warm brown ones. A small offshoot of the cave ended in a grotto padded in straw where a beige and cream speckled pegasus lay, legs folded under its body. She held her breath for a moment as the equine eyes bore into her own: human, wise, ancient, gleaming with an omniscient knowing.

Guinevieve breathed an inaudible greeting to the aged creature, inclining her head in an unspoken understanding, and then waited a beat, as though it would suddenly explain some of the stormy disorientation, tell her the missing pieces of Elris’ curse.

A slight angling of its head motioned to the forking hall, urging her forward. Guinevieve thanked the mare and it responded with a subtle nod of its graceful head.

The trickling of water sounded from a small runnel of rainwater carved into the rock, locked in by a warped wood plank. Soon she came upon breaches in the stone, pockets carved out, inhabited by resources. One stocked with chopped wood piled neatly in the enclave, the next carved as high as the ceiling held stalks of wheat growing from a planter. A series of four smaller shelves housed thyme, basil, mint, sage—on the opposing wall, delicate white buds of chamomile, needles of rosemary, prickled burrs she had never seen, iridescent purple flowers with spiked leaves.

More and more, larger pockets surprised her—ripe, red tomatoes going golden with the subtle flickering of the firelight, warty gourds lounging in spiraled vines, sprouts pushing from deep layers of soil hiding onions, turnips, beets, carrots. How anything was growing under here, baffled her. Xylandovan crops grew miraculously with the thin light filtering through fog—but here, she had no idea.

Suddenly, rounding a corner, she stumbled into a cavern warm with a hearth against the far wall; Elris sat at a stubby round table, and an ancient man turned from the fire with a kettle bubbling in his thin, bony hand, smiling softly at her.

“Ah, Guinevieve, I was hoping you’d show.”

A few moments later, Guinevieve was sat, with an onslaught of paternal ushering, at the table with Elris. The old man busied about at a carved counter behind them, sifting herbs into the kettle, humming to himself. The squat chair creaked and strained with the weight of Elris’ armor.

The man-below didn’t speak until, with shuffling steps, he crossed back to the table, setting the kettle followed by two teacups of thick ceramic before them. His grimace worked its way to a smile as he lowered himself into the chair, staring at the pair with the kind expression of an eccentric grandfather. The decades had stooped his posture and shrunken his bones, but it was clear in his elderly stature he must’ve once been a tall, strapping man. The grey that had taken over whatever color had once pigmented his hair was seeping into a milky white at the roots, and a coarse, wiry beard muddled the lower half of his face, coming to a thin, scraggly point somewhere near his chest. His eyes, lined with webs of thin wrinkles, were a piercing icy blue, but shockingly small in comparison to Guinevieve, who possessed the eyes of a cloud-dweller, overtly massive and suited for the dim, opaque atmosphere. A round, mottled nose stuck out over the haze of his mustache, his cheeks were ruddy and porous, weathered and tanned from a sun she never saw. The man’s hands, materialized from a vast, shapeless black robe, were pocked with weather spots and thinned to paper, green veins protruding alongside the bone. He clasped his hands together in front of him and rested his arms on the table.

“My name is Henrich,” he said in a slightly foreign accent that cut through the lyrical, fluid speech of the cloud-dwellers with a humbling bluntness. “I’m pleased to finally meet you, child, I was expecting you’d find me about this time.

“Sir Elris informed me of your contact with Eva,” he continued, “and I will say, I was awfully surprised to hear from her.”

“Eva?” Guinevieve interrupted, furrowing her brow.

“The lovely sorceress who contacted you through the ring—she was always creative, hiding clues in such unique places. She must’ve foreseen this matrimony, as they often do, and felt there was no better place to leave a gem of such information than in a prophetic token of love. I will say, she was always delightfully witty like this.

“I am indeed, as she so basely named me, the man below the land that she speaks of.” Henrich smiled, thin lips spreading wide. He plucked the top of the kettle and glanced analytically at the steeping herbs before lifting it warily, and pouring two cups, sliding one across the table to Guinevieve. “Drink. A fine tea. I dry it myself.”

The elder waited for her to fulfill his request before continuing. Hesitantly, she took a small sip, nodding appreciatively and Henrich winked in return.

“This is quite a puzzle, and my dear, it is lovely to have such a conundrum walk through my front door. Many years have passed since I’ve had company other than Buggy, the beloved mare, let alone visitors with such an interesting knot to untangle.” He sipped his tea, and a harder gleam shone in his eye, a shadowed edge crossing his features. “You see,” he continued, his voice morphing with his expression from jovial to grave, “my dear Eva is dead.”

A wash of cold shock wrung her out. Elris inhaled sharply, despair slipping through his stoicism.

A sharp whine spliced through the air in her frozen terror. Before she could understand where the sound had come from, a long, elegant arrow was lodged clean through the creature’s neck; the feline had opened its mouth to let loose a roar, but nothing was emitted before it crumpled, toppling off the rock into the water right in front of her—its heavy body setting gentle waves lapping onto the shallow pebbled shore. Paralyzed, her mouth agape, she watched the river redden with its blood and felt the cold droplets of the bloodstained water that had splattered her face and fresh tunic. Sluggishly, the water gave way for the muscled corpse, pushing the dead weight south with the current.

She hadn’t realized she’d dropped her grip on the sword again—it hung lack in the stream, swaying with the current—until she found herself tensing, raising it instinctively in defense of the figure that had appeared suddenly, leaping in a graceful stride atop the boulder where the beast had perched. In its place now stood a tall, blonde man in a tunic camouflaged with the dark green pines, and trousers the shade of shadowed tree bark. He loomed above her in his simple garments, a gold-colored metal vambrace on each wrist glinting with the setting sun, and a heavy belt complete with an array of blades swaying in his steady landing. A massive bow was gripped easily in his thick hand, but no arrow from the quiver slung around his broad back was notched. Guinevieve faltered with her outstretched sword as the man smiled widely, a brilliant grin across his tanned, square face that lifted his pointed, elven ears in a boyishly charming manner. His blonde hair was tied back, but a few tendrils had slipped and framed his face, and he reached up to tuck the stray pieces behind the sharp peaks of his ears. He looked down at Guinevieve in the water with a fierce gleam in a set of solidly emerald eyes, still grinning as he said, in a deep, playful voice, “Welcome to Vallwood.”

My hair unfurled in the water, a floating halo about my head. I lay in the center of the amphitheater, my silk dress soaked and clinging to my skin, the bandages on my gnarled hand ruined and unraveling. Ara knelt behind me with her hands on my jaw. Dal stood above her, an anchor, keeping a slender hand on her love’s shoulder.

Every citizen had gathered in the open-aired chamber. The masked children running wild through Wisterien’s streets had lost their props and now sat with resolved stillness, paralleling their elders. The Biesou waited, so motionless they appeared to be carved of moonstone themselves.

On my back, undulating in the shallow water, I watched what they awaited. The moon, full and swollen with white crystalline glow, was edging closer to the very apex of the sky above the amphitheater. Perhaps it was an illusion of the reflective mineral the city was built with, but it appeared to have grown so large it would stretch to fill the entirety of the opening.

The celestial body was nearing the pinnacle. The lake’s silver water lapped and murmured as collective movement rippled from the steps. The Biesou knelt as Ara did, as if in prayer, submerging their hands. Eloquent whispering rose in pitch and volume, a melodic chanting replacing the silence—the unison uncannily perfect.

I drifted, felt the swelling lift my body, felt the tide rise in hymn. In my peripheral, I could see the steps to the rows of Biesou flooding faster.

The moon reached her peak, spearing silver and white light fiercely into the chamber, an inferno of ethereal luminescence, reflecting off every surface, including the midnight hue of the Biesou’s skin. Their curled horns phosphorescent, pulling moonlight into their souls like conduits. The molten silver streaks within the protrusions lit angelically, auras enveloped bodies entirely.

Celestial climax had come and the Biesou drew the moon to merge with water once again.

Softly peeling back my skin, cleanly cutting into my muscle, my bone, incising bloodlessly into my veins, slicing tenderly into my skull, I flooded with cold, silver light, a pure sterling power fluid and divine. I rose to meet her, prostrate and dissolving. Each syllable from the holy tongue created lunar conjunction, defied eclipse, birthed molecules of iridescent dew coalescing to lift me in tide, to let their mother see the deepest novae within my soul. The Biesou gave me the moon.

A deep, bellowing growl ripped emanated through the cathedral. The walls seemed to shake with its force and hunger. I scanned the surroundings slowly, terror finally setting in, overlaying the numbness that had pushed me this far.

The rising bog rippled, and I could only watch. Something amorphous peaked, breaking the surface. Like tree branches, thick and knotted and sharp, two points were splitting into the air, ten feet apart. They dripped with long strands of scum and creeping aquatic plants, curving like horns.

Water loudly shed from whatever was coming up for air, streaming off of the bulbous shape the horns—yes, definitely I believed them to be horns—were growing from. Ears, mossy and furred and matted with algae, the head of the beast kept rising.

Eyes, set wide apart across a broad nose blinked away the slimy water pouring from it, a glowering, putrid shade of green that burned me to look upon. A snout, steaming the most putrid smell through quivering nostrils—I was gagging, I was burning with the bile in my throat clawing to get up.

The head of a bull in full view. Its face was as tall as I, at least, its body was coming up, humanoid and muscular and all matted with squirming algae. A thick paw-like hand flicked something reptilian from its shoulder, sending an insignificant creature splashing back into the fetid water.

The bull didn’t open its mouth, but I heard its voice booming, felt its torrent of vile breath. “Slay the mistress who feeds,” the voice uttered in a deep, quaking growl, “and one does not go unpunished. I remain hungry. I let human meat cross my skin, plunge into my being, create orifice with each muddy step. I let my pets feast in their desire before I devour the prey they deliver me. You tear at me with your havoc, you reek of human pride, you do not leave. I will not swallow you gracious. I will break your bones in my teeth and savor, suckling the marrow. Naïve girl. Your blood will wash down the foul souring of innocence.”

The minotaur waded a step, sending ripples buffeting my legs; I nearly lost my footing on the stone. He loomed closer, towering above, a writhing mass of hungry terrain made manifest.

Elris’ battle axe hung limp and useless in my hand. Its double-sided blade would be nothing against the swamp that stood before me, a living creature born from every lifeform in the bog.

“Chain of satiation. You came to tear our chain. You came and sunk your teeth into lifeblood in the name of vengeance. Disruptions. Humans are cruel disruptions to the unfathomable consciousness of land,” the voice seethed, guttural, singing my mind with its ear-piercing omnipresence. “The bog allows naught. Ruin for ruin, your wrongs must end in repentance.”